The World Health Organization [WHO] declared the Zika virus and its suspected link to birth defects an international public health emergency on Monday, a rare move that signals the seriousness of the outbreak and gives countries new tools to fight it.

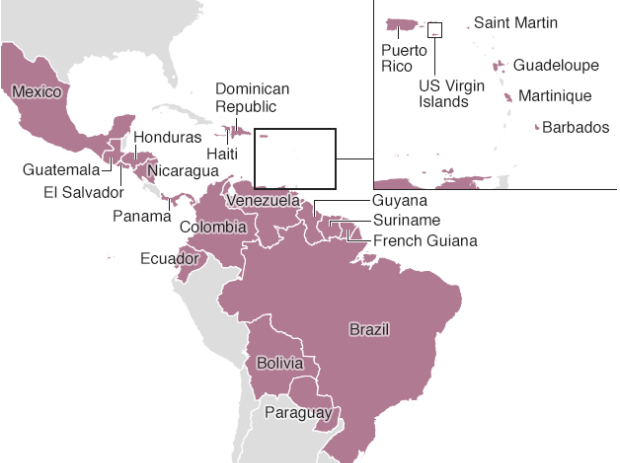

An outbreak of the Zika virus, which is transmitted by mosquitoes, was detected in Brazil in May and has since moved into more than 20 countries in Latin America, including two new ones announced Monday: Costa Rica and Jamaica.

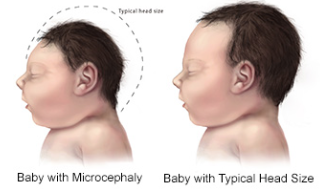

The main worry is over the virus’s possible link to microcephaly, a condition that causes babies to be born with unusually small heads and, in the vast majority of cases, damaged brains.

(New York Times, February 1, 2016)

The WHO did not say so, but concerns about how this virus might affect the Rio 2016 Olympics had a lot to do with Monday’s declaration. Concerns, incidentally, that were only heightened last week after Brazilian Health Minister Marcelo Castro conceded his country is “badly losing the battle” against Zika.

The WHO did not say so, but concerns about how this virus might affect the Rio 2016 Olympics had a lot to do with Monday’s declaration. Concerns, incidentally, that were only heightened last week after Brazilian Health Minister Marcelo Castro conceded his country is “badly losing the battle” against Zika.

One health expert at the epicentre of the outbreak, in Bahia state in northeastern Brazil, accused Ms. Rousseff’s administration of acting too late, and warned that the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro pose a transmission risk.

(Reuters, February 2, 2016)

The point is that the international community has a vested interest in seeing Brazil host a successful Olympics … with full participation. And this declaration is bound to galvanize rich countries, like the United States, to help Brazil contain this virus.

Moreover, there seems to be a direct correlation between the extent to which infectious diseases affect people in rich countries and media coverage of those diseases.

Moreover, there seems to be a direct correlation between the extent to which infectious diseases affect people in rich countries and media coverage of those diseases.

No doubt images of Zika babies with deformed heads are heartrending. But, trust me, we would not be seeing so many of them if the Olympics were being held in Berlin instead of Brazil this summer.

Case in point, the recent outbreak of Ebola dates back to March 2014, when related deaths were limited to West Africa. But the media did not begin covering it as a “public health emergency of international concern” until September 2014, after the first case was diagnosed in the United States. By then, the WHO had already reported 3,000 Ebola deaths in West Africa.

To date, coverage of Zika has focused on the (real) health risks to pregnant women living in or traveling to poor countries throughout the Americas.

But it’s only a matter of time before it begins focusing on the (potential) health risks to Olympic athletes living in rich counties who are preparing travel to Brazil. That is, unless Zika transmissions begin occurring in the United States, as opposed to travellers returning already infected. In which case, there will be viral coverage – complete with scaremongering reports to generate TV ratings and online clicks, just as it was with Ebola.

As it happens, just yesterday the Texas Department of Health Services claimed that it has one documented case of human-to-human transmission. (Infected by a human prick instead of a mosquito prick?) This case involves a man who returned from Venezuela, already infected, and transmitted the virus sexually.

Except that the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is discounting its significance because, like other carriers, the man had travelled from a Zika-affected nation. And neither he nor his partner was pregnant, presumably. The CDC is also discounting this case because there has been no documented case of human-to-human transmission even in any of the Zika-affected nations.

In any event, as Olympic athletes become the focus of media coverage, I urge you to spare a little sympathy for the innocent victims. And I’m referring to victims not only of this infectious disease but also of others, like lower respiratory and diarrheal infections, which kill hundreds of thousands of children every year.

Incidentally, it took almost two years and over 11,000 deaths before the WHO declared all countries Ebola free. Estimates are that it will take 3-5 years and up to 20 million infections before a vaccine or treatment is developed to control the spread of Zika.

In the meantime, the CDC informs us that:

Babies with mild microcephaly often don’t experience any other problems besides small head size…

For more severe microcephaly, babies will need care and treatment focused on managing their other health problems [from vision and hearing loss to intellectual and physical disability].

Health experts cannot overstate that “mild symptoms like rashes and fever” are the only risks Zika poses to anyone who is not pregnant. This stands in reassuring contrast to Ebola, which kills men, women, and children, indiscriminately.

Meanwhile, with Zika coming on the heels of Ebola, you could be forgiven the impression that infectious diseases are suddenly becoming as common as, well, the common cold. But there’s nothing at all sudden about them – as the persistence of tuberculosis, malaria, Hepatitis B, and HIV, to name a few, readily attest. Not to mention chikungunya, which, like Zika, is transmitted to people by mosquitoes.

That said, media alarms about Zika make it easy to overlook persistent concerns about Brazil’s sewage-infested bays and lagoons, which expose locals, and will expose Olympic athletes, to MRSA and all kinds of other waterborne viruses.

Waterborne virus expert Kristina Mena says none of the venues for Rio’s 2016 Olympics are fit from swimmers or boaters. Athletes who ingest three teaspoons of water have a 99 percent chance of being infected by viruses.

(Associated Press, December 2, 2015)

Which means that Olympic athletes have more to fear from fetid water than Zika mosquitoes.

Frankly, holding the Summer Games in Brazil now seems as ill-fated as holding the World Cup in Qatar.

Related commentaries:

Ebola…