To listen to some critics of British colonialism you’d think it was utterly devoid of any redeeming value. But as one who was subjected to it throughout much of his youth, I can attest that this is not so.

To listen to some critics of British colonialism you’d think it was utterly devoid of any redeeming value. But as one who was subjected to it throughout much of his youth, I can attest that this is not so.

Indeed, all one has to do is juxtapose the way education and civil service have floundered in post-colonial countries in Africa with the way they thrived in those countries during colonialism to counter unqualified criticism in this respect.

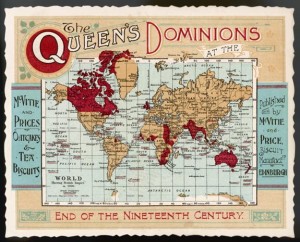

Having said that, let me hasten to assert that nothing, not even a good education and a competent civil service, can possibly justify the dominion British colonialists exercised over native people from India to the Caribbean. Especially because British mercantilism meant raping and pillaging local resources for the benefit of Mother England. Not to mention the practice of racial segregation (i.e. de facto apartheid), which reinforced the dehumanizing nature of colonialism.

More to the point, as British journalist and historian Richard Gott notes in Britain’s Empire: Resistance, Repression and Revolt (2011), no less a person than British PM David Lloyd George telegraphed how colonial officers intended to deal with natives who resisted this dominion when he proudly recalled how, at the 1932 World Disarmament Conference, he:

[D]emanded the right to bomb for police purposes in outlying places [and] insisted on the right to bomb niggers.

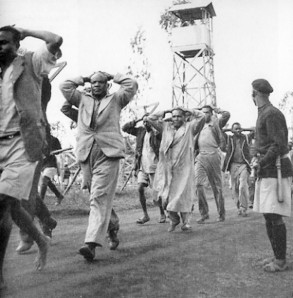

Which brings me to the cruel and unusual punishment colonial officers meted out to natives whose natural pride and human dignity compelled them to resist. Nowhere was this demonstrated in more poignant and persistent fashion than in Kenya during the Mau Mau rebellion throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

For according to the Kenya Human Rights Commission 90,000 Kenyans were executed, tortured or maimed. What’s more 160,000 were detained in conditions that rivaled those their forefathers were subjected to as captured slaves during the “Middle Passage.”

For according to the Kenya Human Rights Commission 90,000 Kenyans were executed, tortured or maimed. What’s more 160,000 were detained in conditions that rivaled those their forefathers were subjected to as captured slaves during the “Middle Passage.”

But where seeking reparations for slavery that ended 150 years ago has always been fraught with obvious (legal) problems, seeking reparations for colonialism that ended just 50 years ago is much less so.

This is why the British government finds itself in the untenable position of having to defend against claims by Kenyans who say they themselves suffered all manner of human rights abuses while being held in detention camps by the British colonial administration during the Mau Mau rebellion.

Lawyers for several victims filed what they clearly hope will be a class-action suit on behalf of all victims demanding an official apology and compensation for pain and suffering.

The claimants’ lawyers allege that Mr Nzili was castrated, Mr Nyingi severely beaten and Mrs Mara subjected to appalling sexual abuse in detention camps during the rebellion…

In his statement Mr Nyingi, 84, a father of 16 who still works as a casual labourer, said he was arrested on Christmas Eve 1952 and held for some nine years. During his detention, in 1959, he says he was beaten unconscious during an incident at Hola camp in which 11 other prisoners were clubbed to death. He says he has scars from leg manacles, whipping and caning.

(BBC, July 17, 2012)

It is noteworthy that the British government admitted this week – for the first time and in a court of law no less – that Kenyans were tortured and ill-treated as alleged. Never mind that it was obliged to do so because the High Court ordered the release of 300 boxes of secret documents recently that not only chronicle the systematic torture and ill-treatment colonial officers meted out, but also expose a conspiracy among British officials to cover up these human rights abuses.

Yet, despite all this, the government is attempting to avoid compensating the direct victims of the Mau Mau rebellion by using the same argument governments have used to avoid compensating the descendants of the victims of slavery; namely, that:

…too much time has passed for a fair trial to be conducted.

(BBC, July 17, 2012)

To be sure, lawyers can raise all kinds of issues as to why, ironically enough, the British government cannot get a fair trial: not least among them is the likelihood of assigning collective guilt to all colonial officers because victims, many of whom are now in their 70s and 80s, would be hard-pressed to identify the offending one(s) in each case; they may even question whether detention during the Mau Mau rebellion was in fact the proximate cause of their injuries.

To be sure, lawyers can raise all kinds of issues as to why, ironically enough, the British government cannot get a fair trial: not least among them is the likelihood of assigning collective guilt to all colonial officers because victims, many of whom are now in their 70s and 80s, would be hard-pressed to identify the offending one(s) in each case; they may even question whether detention during the Mau Mau rebellion was in fact the proximate cause of their injuries.

All the same, if the British government has any regard for what little redeeming value its legacy of colonialism retains, it would consider it a moral imperative to move post-haste to negotiate a victims’ fund with the Kenyan government from which all victims can seek relatively fair compensation … in Kenya.

Incidentally, this would (and should) not absolve the government of the categorical imperative to pursue and prosecute every British official implicated in these human rights abuses: from the Secretary of State in London to the camp guard in Kenya, and not just those who executed them but those who participated in the conspiracy to cover-up these abuses for so many years as well. Indeed, these British officials should be pursued and prosecuted with the same dogged zeal with which officials who collaborated with the Nazis in the torture and ill-treatment of the Jews are still being pursed and prosecuted to this day….

Of course, colonial rebellions were not nearly as persistent, and were not put down with nearly as much brutality in other colonies, as was the case in Kenya (the American rebellion excepted). But if the High Court were to establish the precedent that victims of colonial-era abuses could seek damages in British courts, I have no doubt that thousands of claimants would show up in London to seek redress from every place on earth that was subjected to British dominion.

In which case the British government would be well-advised to initiate government-to-government settlements of all such cases instead of allowing any of them to proceed to trial – especially with all of the opening of old wounds (on both sides) that would entail.

Mind you, even if the High Court were to rule that victims of colonial abuse have no recourse in British courts, the reputational damage to Britain of such an inequitable ruling would far outweigh any amount the Kenyan and other post-colonial governments could reasonably demand be placed in compensation funds for colonial abuses.

Accordingly, I fully expect Britain, at long last, to do the right thing: apologize and pay, pursue and prosecute!

Related commentaries:

U.S. finally apologizes for slavery…

Kenya … war crimes