Muhammad Ali was “The Greatest of All Time” – even if he said so himself. But what made him undeniably so had to do with what he did (and said) outside, as much as inside, the boxing ring.

Muhammad Ali was “The Greatest of All Time” – even if he said so himself. But what made him undeniably so had to do with what he did (and said) outside, as much as inside, the boxing ring.

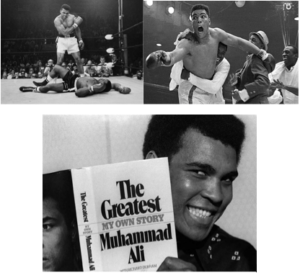

Of course, his opponents – from Sonny Liston to Joe Frazier and George Foreman – would readily attest that he really did “float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.” And, with all due respect to the likes of Joe Louis, Floyd Patterson, and Sugar Ray Leonard, Ali was easily the most charismatic and entertaining boxer in the history of their sport.

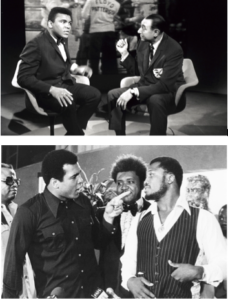

No doubt the way his “Louisville lip” hyped up fights and psyched out fighters contributed to his success. And legendary sportscaster Howard Cosell deserves honorable mention for playing straight man and comic foil for much of the truly poetic trash talking that made Ali famous.

No doubt the way his “Louisville lip” hyped up fights and psyched out fighters contributed to his success. And legendary sportscaster Howard Cosell deserves honorable mention for playing straight man and comic foil for much of the truly poetic trash talking that made Ali famous.

Never mind the inconvenient truth that he copied much of his “I am the greatest,” self-promoting schtick from the flamboyant professional wrestler Gorgeous George (Google him); or that Ali played the intra-race card, most notably by mocking his Thrilla-in-Manila opponent, Joe Frazier, an “Uncle Tom,” a “gorilla,” and the “white man’s champion.” (I suspect Ali’s taunts gave the preternaturally black and proud Frazier a terminal racial complex, much like that which the humiliating Senate hearings for Clarence Thomas’s appointment to the Supreme Court gave him.)

Yet nothing is more telling about Ali “inside the ring” than the fact that he does not even rank among boxers with the “greatest unbeaten record of all time.” That distinction belongs to the likes of Joe Calzaghe (46-0, 32 KOs), Rocky Marciano (49-0, 43 KOs), and Floyd Mayweather (49-0, 26 KOs). Surely any of these boxers has a more legitimate claim to the title as the greatest fighter of all time than Ali (56-5, 37 KOs).

This brings me to Ali “outside the ring,” which accounts for so much of his greatness.

He claimed in his 1975 autobiography that he threw the gold medal he won at the 1960 Summer Olympics into the Ohio River – after a “whites-only” restaurant refused to serve him and a friend. But this reportedly apocryphal story was just his poignant way of protesting the shame and injustice of championing America abroad, only to be treated like a second-class citizen at home … in Jim Crow America.

He described his conversion to Islam in 1965 as one of the most important milestones in his life. This led to the very public show he made of denouncing his “slave name,” Cassius Clay, and demanding to be called by his Muslim name, Muhammad Ali.

He described his conversion to Islam in 1965 as one of the most important milestones in his life. This led to the very public show he made of denouncing his “slave name,” Cassius Clay, and demanding to be called by his Muslim name, Muhammad Ali.

But almost as many blacks as whites regarded this as a betrayal. Bear in mind that Ali pledged his allegiance to the Nation of Islam, which was then, and remains to this day, an unabashedly black separatist … cult. The only equivalent I can think of today, with respect to those feelings of betrayal, is Stephen Curry denouncing Hillary Clinton and the Democratic Party and proclaiming his support for Donald Trump and the Republican Party.

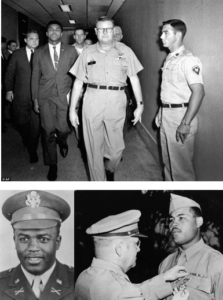

In any event, nothing sealed Ali’s legacy as the greatest in this context quite like his refusal to be inducted into the armed services. Here is the now famous way he justified his conscientious objection to going to war in Vietnam:

Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?

Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong. No Viet Cong ever called me nigger.

(BBC, June 4, 2016)

He was arrested in 1967 and convicted as a draft dodger. He faced five years in prison and a $10,000, but was released on bond pending appeal. Unfortunately, the New York Athletic Commission summarily banned him from boxing and revoked his heavyweight title.

He was arrested in 1967 and convicted as a draft dodger. He faced five years in prison and a $10,000, but was released on bond pending appeal. Unfortunately, the New York Athletic Commission summarily banned him from boxing and revoked his heavyweight title.

Jackie Robinson was probably the only black athlete more famous than Ali at the time; not least because the then retired Robinson traveled and marched with Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. during the height of the Civil Rights Movement.

Which is why it was so significant when Robinson condemned Ali as follows:

I think that he’s hurting, I think, the morale of a lot of young Negro soldiers over in Vietnam. And the tragedy to me is that Cassius has made millions of dollars off of the American public, and now he’s not willing to show his appreciation to a country that is giving him, in my view, a fantastic opportunity, hurts a great number of people.

(“Eyes on the Prize,” PBS American Experience, August 23, 2006)

To fully appreciate his condemnation it might be helpful to know that Robinson was drafted to serve during World War II. Not to mention that heavyweight-boxing champion Joe Louis and other celebrities enlisted to serve during that war.

But, ironically, it was Ali’s defiant refusal to be drafted for Vietnam that made him so heroic. Here is how civil rights firebrand Stokely Carmichael hailed Ali — courtesy of Dave Zirin’s book, A People’s History Of Sports In The United States: 250 Years of Politics, Protests, People, and Play (2009):

Lots of people refused to go…

But no one risked as much from their decision not to go to war in Vietnam as much as Muhammad Ali. And his real greatness can be seen in the fact that, despite all that was done to him, he became even greater and more humane.

Of course, as opposition to the war grew, the athletic commission seized the opportunity to reinstate Ali’s boxing license in 1970. But, by then, he had lost over three years of boxing in his prime – from age 25 to 29. In a unanimous but anticlimactic decision, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned his conviction in 1971.

The point is that I can’t imagine any other athlete risking so much to stand on any principle. In fact, political activism for most athletes these days is limited to posting feckless tweets like #BringBackOurGirls, or wearing T-Shirts with fashionable slogans like “Hands Up Don’t Shoot” and “I Can’t Breathe.”

The point is that I can’t imagine any other athlete risking so much to stand on any principle. In fact, political activism for most athletes these days is limited to posting feckless tweets like #BringBackOurGirls, or wearing T-Shirts with fashionable slogans like “Hands Up Don’t Shoot” and “I Can’t Breathe.”

Nothing is more cynical in this respect than headlines about Tiger Woods “leading the golf world in celebrating the life of Muhammad Ali.” This, after all, is the same Tiger who was so zealous about protecting his brand, he conscientiously objected to being called black, preferring what he deemed the more marketable classification, cablanasian.

Not to mention the truly selfish precedent no less an athlete than Michael Jordan set. He was so zealous about protecting his brand, he conscientiously objected to endorsing a black candidate for the U.S. Senate – from his home state of North Carolina no less.

Here is the now infamous way Jordan justified his conscientious objection:

Republicans buy shoes, too.

(Forbes, September 22, 2011)

Frankly, it’s easy to see why no athlete has sacrificed more for the national advancement of black people than Muhammad Ali. And, with respect to having the courage of one’s convictions, no athlete has stood as a better role model for us all.

Meanwhile, other celebrities are competing with famous athletes to pay homage to Ali with tweets that are clearly intended to draw attention to them more than to honor him. Exhibit A is Donald Trump. This, of course, is the same Islamophobic Trump who, just months ago, was tweeting that he can’t think of a single Muslim worthy of presidential praise as an American hero – Muhammad Ali and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar be damned (or banned?)

Later in life, Ali received numerous accolades for his humanitarian, interfaith, and charitable works. For example, both Sports Illustrated and the BBC named him sportsman of the century in 1999; President George W. Bush awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2005; and his hometown of Louisville opened the Muhammad Ali Center also in 2005, which chronicles his life and promotes tolerance and respect among all people.

But it seemed a fate as ironic as it was cruel when he was diagnosed in 1984 with Parkinson’s disease. There are credible but conflicting reports that repeated boxing blows to his head caused it. Whatever the case, Parkinson’s soon reduced this man who once floated like a butterfly and stung like a bee, to one so stricken with tremors he could hardly … pee. Perhaps even worse, though, it put a zip on his Louisville lip….

Ali’s condition first shocked most of us during the Opening Ceremony for the 1996 Centennial Olympics in Atlanta. When he suddenly appeared as the final torch bearer, it was heartwarming and heartbreaking in equal measure to see him battling his unruly tremors just to light the flame. In that moment I made a causal link between boxing and his pitiable condition. My love for the “sweet science” of boxing has never been the same.

But it speaks volumes about his character that the withering ravages of Parkinson’s did not cause him to shun public appearances. Most notably, he continued fundraising for his many charities and foundations, including the Special Olympics and the Parkinson Society.

But it speaks volumes about his character that the withering ravages of Parkinson’s did not cause him to shun public appearances. Most notably, he continued fundraising for his many charities and foundations, including the Special Olympics and the Parkinson Society.

Sadly, this included being propped up for photo ops with all kinds of people. This, even though the resulting image often looked like a screenshot from Weekend at [Ali’s]. But they did it because a selfie, even with “The Greatest” looking like a dead man, is by definition more about them than him.

Ali died late Friday at a hospital in Arizona. He is survived by nine children from four wives. Which compels one to hope they do not defile his legacy by fighting over his fortune, the way the heirs of MLK and James Brown defiled their respective legacies by doing so.

Perhaps even more dismaying, though, are reports that Ali’s children are just lying in wait to shock the world with tales about how the greatest as a boxer was anything but as a husband and father.

He was 74.

Farewell, Champ.