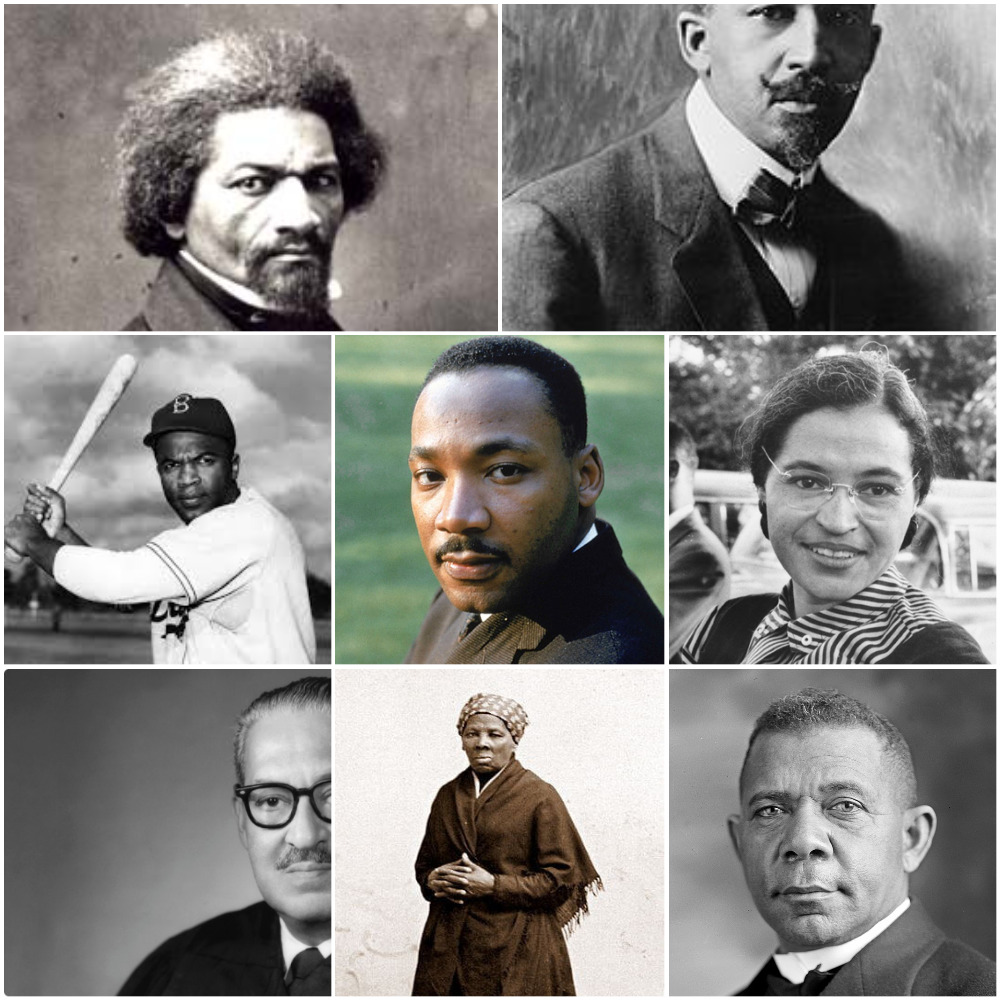

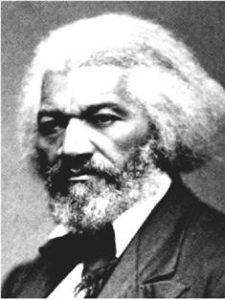

I have been making this claim for decades. It’s based primarily on the fact that Frederick Douglass personified both the contradictions and promises that define America’s founding documents. And he did so like nobody else has or ever could.

Unfortunately, even black historians have been so indoctrinated with white historiography, they invariably try to qualify my claim as follows:

You mean the greatest (black) figure … don’t you?

But no, I mean, and have always meant, the greatest figure, period! This is why I’ve felt so dismayed over the years as I watched Douglass suffer one historical slight after another.

It’s bad enough that white historians (and politicians) rarely accord him even an honorable mention when discussing the greatest Americans. But it smacks of fratricide that black ones accord him little more.

Only this explains why Douglass was never the obvious choice when it came to honoring the first black American with, among other things, a

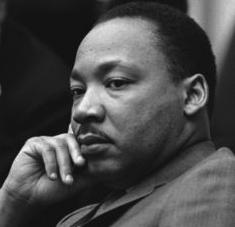

- monument on the National Mall (Martin Luther King Jr. (MLK))

- national holiday (MLK)

- picture on any dollar bill (Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth being considered)

- picture on a postage stamp (Booker T. Washington)

And don’t get me started on the new National Museum of African American History and Culture choosing the life and times of Oprah Winfrey for its first special exhibition. I decried the museum’s myopic and craven choice, as well as Oprah’s self-adulating and self-indulgent acceptance of it, in “African American Museum Paying Trumpian Tribute to Oprah. Shame!” June 11, 2018.

No wonder, then, that TIME did not include Douglass on its definitive list of “The 100 Most Significant Figures in History,” which it published in 2013. The top five, in order, were Jesus, Napoleon, Muhammad, William Shakespeare, and Abraham Lincoln. But the list also included such notable Americans as George W. Bush (#36), Joseph Smith (#55), and Grover Cleveland (#98).

Of course, MLK is often hailed as the greatest (black) figure America has ever produced. But there are many compelling reasons to hail Douglass as such. Here is how I delineated some of them in “Mall at Last, Mall at Last, Thank God Almighty a Black Is on the Mall at Last,” November 14, 2006.

____________________

Douglass was born in slavery; MLK was born in freedom.

Douglass was born in slavery; MLK was born in freedom.- Douglass spent his formative years on a plantation scrapping with his master’s dogs for food to eat; MLK spent his in relative luxury dining with America’s black elite.

- Douglass taught himself to read and write; MLK attended America’s best schools, including Morehouse College and Boston University.

- Douglass escaped from slavery, settled in the North, and began his political activism by leading challenges to segregation laws, which were as strictly enforced in the Antebellum North as they were in the Deep South; MLK graduated from university, settled in the South, and began his political activism by accepting calls to lead blacks – who had already begun the now-seminal Montgomery Bus Boycott.

- Douglass had no peer among blacks; MLK had Stokely Carmichael and Malcolm X – whose message of self-defense and black nationalism resonated more with young blacks (for whom ‘by any means necessary’ was far more liberating and empowering than ‘I have a dream’).

- Douglass left no trail of marital infidelities in his wake that could compromise judgement of the content of his character; MLK did, so much so that, in my resigned attempt to defend his character, I was constrained to title my commentary “Martin Luther King Jr Was Also a Womanizer, So What?” January 4, 2006.

Douglass lived long enough (to age 77) not only to see his dream of abolition fulfilled, but also to become a professional man (as a US Marshall and recorder of deeds), an international statesman (as US Ambassador to Santo Domingo and Haiti), and a political champion for yet another cause (women’s suffrage); MLK died too soon (at age 39) not only to see his dream of racial equality fulfilled, but also to pursue any ambition beyond the struggle for civil rights.

Douglass lived long enough (to age 77) not only to see his dream of abolition fulfilled, but also to become a professional man (as a US Marshall and recorder of deeds), an international statesman (as US Ambassador to Santo Domingo and Haiti), and a political champion for yet another cause (women’s suffrage); MLK died too soon (at age 39) not only to see his dream of racial equality fulfilled, but also to pursue any ambition beyond the struggle for civil rights.- Douglass’s published works on the fight for freedom from slavery are voluminous; MLK’s on the struggle for civil rights are modest by comparison (for obvious reason). (I refer you to articles from one of Douglass’s many newspapers, The North Star, and to his three autobiographies Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass — an American Slave, My Bondage and My Freedom, and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. It might also interest you to know that eyewitness accounts – by the likes of famous abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison – suggest that Douglass was every bit the orator MLK was. Indeed, it’s arguable that his “What to the slave is the 4th of July?” speech, which he delivered on July 5, 1852, was even more provocative and inspiring than MLK’s ‘I Have A Dream’ speech, which he delivered on August 28, 1963.

__________________

Alas, I cannot help Douglass get the recognition (and honors) he deserves. I just don’t have the political or literary influence.

Which brings me to Adam Gopnik and his essay in the October 15, 2018 issue of The New Yorker. It’s titled “The Prophetic Pragmatism of Frederick Douglass” and has this defining and intriguing subtitle:

He escaped from slavery, and helped rescue America.

As I read it, I felt like I did when I was in grade school and my big brothers were fending off schoolyard bullies for me. As a critically acclaimed novelist, reporter, lecturer and social critic, Gopnik has the kind of influence I lack. He has always struck me as a more sober, less acerbic Christopher Hitchens …

As I read it, I felt like I did when I was in grade school and my big brothers were fending off schoolyard bullies for me. As a critically acclaimed novelist, reporter, lecturer and social critic, Gopnik has the kind of influence I lack. He has always struck me as a more sober, less acerbic Christopher Hitchens …

In any event, I strongly recommend you read and share his essay. Because the more you do, the more likely Douglass will get his due.

As it happens, Gopnik ended his essay by juxtaposing Douglass’s biography with that of no less a person than Abraham Lincoln. In doing so, he mirrored the juxtaposition of Douglass and MLK’s I cited above.

Here’s a little Gopnik teaser:

Lincoln remains the saint of American democracy, yet his ascent from the backwoods to the White House was, for all its rigors, a far easier ride. …

In his legacy as prophetic radical and political pragmatist, in the almost unimaginable bravery of his early journey and the resilience of his later career, in his achievements as a writer, activist, crusader, intellectual, father, and man, the claim that [Douglass] was the greatest figure that America has ever produced seems hard to challenge.

There’s no denying that Gopnik’s essay amounts to an authoritative vindication of my assertion. Accordingly, I rest my case.

Hail, Douglass!

Related commentaries:

Oprah exhibition…

The Mall at last…

Woman on dollar bill…

Gopnik: Prophetic … Douglass…

Christopher Hitchens…