My, how far we’ve come from the 1980s, when Tom Wolfe glorified investment bankers as “masters of the universe” in Bonfire of the Vanities. For inasmuch as Wolfe parodied the confluence of their sins (most notably, racism and greed), even he did not fully appreciate the utter venality, vacuity, and depravity of the financial transactions they mastered on Wall Street.

By contrast, just weeks ago JPMorgan Chase and Barclays joined the rogues’ gallery of banks that are now openly and notoriously beset by the corrupt, illegal, and incompetent practices of their putative masters of the universe. In fact, what seemed like an unfolding pandemic of banking scandals moved me to lament just weeks ago that the banking industry could not fall any lower into disrepute. Well, it has.

For it was unthinkable and unconscionable enough that investment bankers induced poor people to take on mortgages they could not afford just to bundle these “subprime mortgages” and peddle them as triple-A asset-backed securities; or that they used depositors’ money to gamble on everything from currency exchanges to soybean prices; or that they rigged the interbank lending rate to extract more interest payments on everything from car loans to credit cards.

But now come reports this week that, on top of all that, investment bankers were operating as little more than bagmen for terrorists and drug kingpins – all of which suggesst that investment banking these days amounts to little more than a sophisticated game of Three Card Monte.

But now come reports this week that, on top of all that, investment bankers were operating as little more than bagmen for terrorists and drug kingpins – all of which suggesst that investment banking these days amounts to little more than a sophisticated game of Three Card Monte.

From 2001 to 2007, HSBC affiliates sent almost 25,000 transactions involving Iran worth over $19bn dollars through HBUS and other US accounts, while concealing any link with Iran in 85% of the transactions…

HSBC accepted more than $15bn in cash from subsidiaries in Mexico, Russia and other countries at high risk of money laundering but failed to conduct any monitoring of these bulk cash transactions between mid-2006 and mid-2009…

HSBC knew of lax anti-money laundering practices at its Mexican subsidiary HBMX, which had dated back to its purchase in 2002. HBMX was warned, on at least two occasions, by Mexican authorities that drug money was probably being laundered through HBMX accounts.

(BBC, July 17, 2012)

Hell, I doubt even Gordon Gekko, the de facto patron saint of investment bankers, had in mind making money off terrorism and drug smuggling when he famously pronounced that “greed is good.” For even he could probably foresee the untenable consequences of such transactions to which these latter-day, money-grubbing masters of the universe – not just at HSBC but at all banks – have turned a blind eye:

The problem here is that some international banks abuse their U.S. access. Some allow affiliates operating in countries with severe money laundering, drug trafficking, or terrorist financing threats to open up U.S. dollar accounts without establishing safeguards at their U.S. affiliate…

In an age of international terrorism, drug violence in our streets and on our borders, and organized crime, stopping illicit money flows that support those atrocities is a national security imperative.

(Senator Carl Levin, chairman of the Senate Permanent Committee on Investigations, Senate Home Page, July 17, 2012)

But lest you think U.S. authorities are just discovering what a metastasizing cancer international money laundering has become, consider this report from over two years ago:

But lest you think U.S. authorities are just discovering what a metastasizing cancer international money laundering has become, consider this report from over two years ago:

Wachovia admitted it didn’t do enough to spot illicit funds in handling $378.4 billion for Mexican-currency-exchange houses from 2004 to 2007. That’s the largest violation of the Bank Secrecy Act, an anti-money-laundering law, in U.S. history — a sum equal to one-third of Mexico’s current gross domestic product. Wachovia’s blatant disregard for our banking laws gave international cocaine cartels a virtual carte blanche to finance their operations.

(Jeffrey Sloman, federal prosecutor, June 29, 2010)

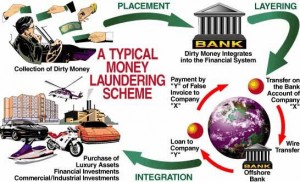

And if you’re wondering why investment bankers would prostitute their intelligence and risk their banks’ reputation by devising all kinds of Euclidean schemes to launder dirty money, consider that, while such schemes garnered standard fees from 6-8 percent during the 1980s and were therefore the exception, they garner up to 25 percent today and have therefore become the rule.

But the bottom line is that, at this point, investment bankers make used-car salesmen seem reputable….

Related commentaries:

Banking scandal redundant…