In “G8 Summit ’05: Rich Nations Pledge (again) to End Poverty,” May 27, 2005, I decried the way extreme poverty persisted in developing countries, despite global pledges and efforts to end it. Here is an excerpt.

__________________

It is a glaring indictment of our shared humanity that rich countries revel in obscene wealth, while poor ones wallow in extreme poverty.

Yet, for more than fifty years, people of conscience have pleaded to no avail for rich countries to help alleviate world poverty by redistributing a little of their wealth. Indeed, when the United Nations passed a resolution thirty-five years ago to cut world poverty in half by 2015, it seemed naïve at best.

Yet, for more than fifty years, people of conscience have pleaded to no avail for rich countries to help alleviate world poverty by redistributing a little of their wealth. Indeed, when the United Nations passed a resolution thirty-five years ago to cut world poverty in half by 2015, it seemed naïve at best.

Sure enough, the pledges rich countries made pursuant to that resolution never amounted to much more than political grandstanding. And, therein lies the perennial fallacy of rich countries making pledges to help poor ones. (Just ask the Indonesians how much of the billions pledged for Tsunami relief has actually materialized.)…

It must be noted, however, that no discussion or criticism of the failure of rich countries to honor their aid pledges would be complete without acknowledging the even more scandalous failure of poor countries to manage the aid they receive responsibly. After all, it has become axiomatic that corruption is part of the culture of life in most developing countries. With the end of the Cold War, however, donor nations no longer have as much strategic interest in these countries. They are now less inclined to turn a blind eye to the rampant misappropriation and gross mismanagement of aid that was so customary.

Therefore, concomitant with challenging rich countries to increase and fulfill their pledges, we must require poor countries to demonstrate more transparent accounting for (and sensible use of) foreign aid. Because, despite shortchanging and other shortcomings, the cumulative data on the aid rich countries have donated compels one to wonder why poor countries have not done more to alleviate extreme, chronic poverty in their midst.

__________________

The good news is that the international community has done a lot since then to “make poverty history,” notwithstanding my abiding criticism.

The number of people living in extreme poverty is likely to fall for the first time below 10% of the world’s population in 2015, the World Bank said on Sunday…

Across the planet, the number of people living in extreme poverty has dropped by more than half since 1990, when 1.9 billion people lived on under $1.25 a day, compared to 836 million in 2015, according to the UN…

Replacing [the poverty alleviation goals] are the Sustainable Development Goals, a set of 17 goals to combat poverty, inequality and climate change by 2030 – with ending extreme poverty for all people everywhere, a key target.

(UK Guardian, October 4, 2015)

The bad news is that poverty across Africa persists at more than three times the level it does across Asia. Specifically, according to this same World Bank report, more than one third of Africa’s population remains mired in extreme poverty.

In fact, it stands as a historic contradiction that the more aid Africa received the poorer Africa became. But this has had almost as much to do with rich countries extracting onerous debt-repayments terms as with African leaders embezzling aid, systematically, and ethnic/religious conflict undermining development, chronically.

Over the past 60 years at least $1 trillion of development-related aid has been transferred from rich countries to Africa. Yet real per-capita income today is lower than it was in the 1970s, and more than 50% of the population — over 350 million people — live on less than a dollar a day, a figure that has nearly doubled in two decades.

Even after the very aggressive debt-relief campaigns in the 1990s, African countries still pay close to $20 billion in debt repayments per annum, a stark reminder that aid is not free.

(Wall Street Journal, March 21, 2009)

In addition to joining other westerners in calling for debt relief, I have lamented the aid paradox in such commentaries as “Fatal Assistance to Haiti. Oxymoron Intended,” February 3, 2015.

In addition to joining other westerners in calling for debt relief, I have lamented the aid paradox in such commentaries as “Fatal Assistance to Haiti. Oxymoron Intended,” February 3, 2015.

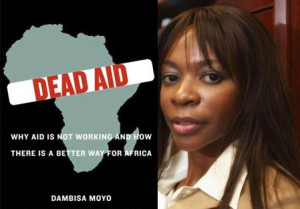

But, apropos of my abiding criticism, it is far more noteworthy that young African leaders, like Dambisa Moyo of Zambia, are actually championing a paradigm shift from Western-style aid to Chinese-style investments:

My frustration as an African is that, here is Bill Gates, he did not reach success by relying on aid…

His ability to transform the African condition, indeed the human condition, would be far more effective if he went to Africa and did something truly innovative like setting up a university, or an engineering school, or a massive Microsoft plant…

Ultimately one takeaway about why aid is problematic is that it undermines the accountability of governments in these countries [that] are able to abdicate their responsibility of providing the public goods, like education, healthcare, national security, infrastructure [which] is the only mechanism by which we are able to hold them accountable and thus have proper liberal democracies in place.

(Slate, May 22, 2013)

Hope springs eternal….

Related commentaries:

G8…

Fatal assistance…