I’ve read enough about Gabriel García Márquez (Gabo) to know that he was that rare writer who was as critically acclaimed as he was commercially successful. That he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982 and enjoyed J.K. Rowling-like book sales attest to this.

I’ve read enough about Gabriel García Márquez (Gabo) to know that he was that rare writer who was as critically acclaimed as he was commercially successful. That he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982 and enjoyed J.K. Rowling-like book sales attest to this.

Yet how fitting in this age of Twitter that most people, including those who should know better, are eulogizing this “greatest writer in the Spanish language since Cervantes” as if he wrote only one novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Worse still, the vast majority of those eulogizing him probably know no more about his works than they do about Stephen Hawking’s. I remember well in the late 1990s when, oddly enough, people wanted to appear both hip and intelligent. It seemed de rigueur back then to rave about the brilliance and insightfulness of Hawking’s A Brief History of Time.

Yet, whenever I asked people to elaborate on what made this book so compelling, I was invariably met with the kind of doe-eyed stutter one gets from a child trying to explain that it wasn’t him who ate the cookies … with his mouth full. I’m not sure what it says about me that I had no difficulty admitting that I found his sojourn into black holes and quarks so friggin’ inscrutable I did not get beyond the first few pages.

The point is, if you were to ask anyone waxing literary about the greatness of One Hundred Years of Solitude to elaborate, chances are very good that, after some trite fluff about magical realism, you too will get that very telling doe-eyed stutter. And don’t bother asking about his lesser-known works because chances are you’d be lucky to even get the title of any of them.

I should disclose here that this celebrated novel was among others, including No One Writes to the Colonel and The Autumn of the Patriarch, I was required to read for a comparative literature course I took in college. Yet, just as it was when pretending to be impressed by Hawking’s writing was in vogue, I have no difficulty admitting today that Gabo’s writing did not leave much of an impression on me. Love in the Time of Cholera, arguably his second most popular novel, had yet to be published.

Interestingly enough, though, as a bit of a lark, a close friend has been urging me for years to read Memories of My Melancholy Whores. I’m not sure why she thinks I would be more impressed by, or able to relate to, this particular novel. But I might finally read it as a way of paying my last respects.

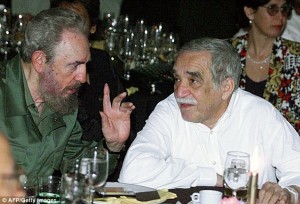

Having said all that, what I found most interesting about Gabo’s life were the political realities that, on the one hand, forced him to flee his native Columbia, while on the other, won him the admiration and affection of world leaders like Bill Clinton. Most notably, Gabo was an uncompromising leftist, which no doubt explains why the likes of Fidel Castro were so solicitous of his political imprimatur.

Having said all that, what I found most interesting about Gabo’s life were the political realities that, on the one hand, forced him to flee his native Columbia, while on the other, won him the admiration and affection of world leaders like Bill Clinton. Most notably, Gabo was an uncompromising leftist, which no doubt explains why the likes of Fidel Castro were so solicitous of his political imprimatur.

But when fellow Latino and estranged friend Mario Vargas Llosa emulated him by winning the Nobel Prize, I could not resist using the occasion to mock Gabo’s reputed self-righteousness:

It would be remiss of me not to admit the schadenfreude I experienced from the fact that the announcement of this award was probably greeted with quiet resentment by two of Vargas Llosa’s most notorious nemeses:

One is Nobel Laureate Gabriel García Márquez, his erstwhile best friend, whom Vargas Llosa gave a black eye in 1976 for reportedly counseling his wife to leave him after he (Vargas Llosa) had an affair. The two men did not speak for over 30 years after that bout, and reports are that their relationship today is cordial at best.

The other is former Cuban dictator Fidel Castro who became the target of Vargas Llosa’s poison pen after he renounced the leftist ideology he shared with old comrades like García Márquez to become one of the world’s most celebrated right-wing intellectuals … much to my dismay.

(“Vargas Llosa Awarded Nobel Prize for Literature,” The iPINIONS Journal, October 8, 2010)

To be fair, apropos of his famous falling out with Vargas Llosa, it might just be that Gabo was also an uncompromising romantic:

Shoot me. There is no greater glory than to die for love.

(‘Life in the Time of Cholera,’ p. 82)

A sentiment that rivals Patrick Henry’s “Give me liberty or give me death!” No?

Meanwhile, moments after Gabo’s death notice yesterday, Columbian President Juan Manuel Santos delivered a televised address to the nation in which he hailed him as “the most admired and cherished compatriot of all time” and then declared three days of mourning.

Meanwhile, moments after Gabo’s death notice yesterday, Columbian President Juan Manuel Santos delivered a televised address to the nation in which he hailed him as “the most admired and cherished compatriot of all time” and then declared three days of mourning.

In doing so, however, Santos might have, unwittingly and ironically, betrayed the kind of unrequited love Gabo famously made a virtue of in Life in the Time of Cholera. After all, unlike fellow exile Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who eventually made it back to his homeland of Russia, Gabo died not in his homeland of Columbia, where he is evidently so beloved, but in his adopted country of Mexico, where he lived from the early 1960s until his death.

He reportedly suffered from dementia and other maladies in recent years and finally died on Thursday. He was 87.

Farewell, Gabo.

* This commentary was originally published yesterday, Friday, at 7:28 pm