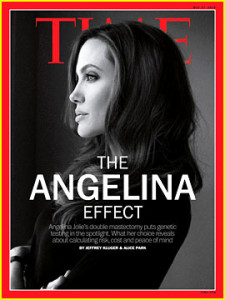

On Tuesday the New York Times published an op-ed by actress Angelina Jolie on her decision to have a double mastectomy. Almost immediately she became the subject of media beatification the likes of which we have not seen, well, since Barack Obama announced his candidacy for president of the United States in 2008.

On Tuesday the New York Times published an op-ed by actress Angelina Jolie on her decision to have a double mastectomy. Almost immediately she became the subject of media beatification the likes of which we have not seen, well, since Barack Obama announced his candidacy for president of the United States in 2008.

But let me hasten to clarify: I fully understand why she’s being hailed as a saint – especially to women with that dreaded BRCA (1 or 2) gene that makes them so susceptible to breast and ovarian cancer. It’s just that you’d never know from this coverage that tens of thousands of women, including lesser-known celebrities, have talked openly about having a double mastectomy.

Alas, in our celebrity-obsessed culture, having an A-lister like Jolie do so somehow makes it okay, perhaps even fashionable. This obsession clearly explains why the media made such a big deal about NBA player Jason Collins coming out as gay.

But surely it takes courage for any woman to deal with breast and ovarian cancer: whether prophylactically – as Jolie did/is doing, or by trying desperately to treat them – as far too many women are fated to do each year. The point is that all women dealing with this medical crisis should be supported, unconditionally.

But surely it takes courage for any woman to deal with breast and ovarian cancer: whether prophylactically – as Jolie did/is doing, or by trying desperately to treat them – as far too many women are fated to do each year. The point is that all women dealing with this medical crisis should be supported, unconditionally.

What I don’t understand, however, is the oxymoronic notion that Jolie is de-sexualizing female breasts by making public her personal medical choice. Most notable in this respect is an article by Professor Alexandra Bradner in yesterday’s edition of Salon titled, “Angelina Jolie’s most thrilling decision: Robbing her breasts of their cultural power.”

Bradner’s subtitle says it all:

Male film critics will have less to ogle, but perhaps now audiences will equate her physicality with strength.

The problem with her thesis of course is that, thanks to the prevalence of elective breast implants among actresses, male film critics and moviegoers alike have had much more to ogle for years now. Perhaps Bradner is unaware that Jolie did not opt to remain au naturel (i.e., flat chested). That would have been heroic, and truly worthy of media beatification. Instead, she got a boob job … too.

The problem with her thesis of course is that, thanks to the prevalence of elective breast implants among actresses, male film critics and moviegoers alike have had much more to ogle for years now. Perhaps Bradner is unaware that Jolie did not opt to remain au naturel (i.e., flat chested). That would have been heroic, and truly worthy of media beatification. Instead, she got a boob job … too.

Which raises the questions: Why hail Jolie as the patron saint of breast-cancer survivors when all she did was elect to look like every other actress in Hollywood who makes a living by showing off the most titillating fake breasts money can buy? And, apropos of all this praise, am I the only one who recalls how she was universally ridiculed just last year for posing on the red carpet at the Academy Awards as if she were striking a standing, semi-clothed pose for Penthouse magazine…? Hell, far from “robbing her breasts of their cultural power,” she’s maintaining her (self-objectifying) sex-symbol status by any means necessary.

For the record, this surgery for the sake of vanity is hardly limited to actresses:

For reasons we don’t fully understand, rates of CPM [aka double mastectomies] are on the rise. Between 1998 and 2003, rates of CPM in the United States more than doubled from 1.8 to 4.5 percent. And, among women having a mastectomy instead of lumpectomy, the rate of CPM increased from 4.2 to 11.0 percent. Women choosing CPM tend to be younger, Caucasian and have a higher educational level.

(“Understanding Breast Cancer,” Susan G. Komen Foundation)

Not to mention that, for some, a woman getting breast implants after having a double mastectomy is rather like a drunk taking up smoking after giving up alcohol. Just ask Sharon Osborne who, like Jolie, elected to have a double mastectomy – not because she was diagnosed with cancer, but because she had that dreaded gene:

‘I wasn’t diagnosed with cancer, but I had the gene and one of my breasts was in a really bad state because of the implant, she said, adding as a word of advice, ‘never have [implants] by the way’

(People, November 5, 2012)

Notwithstanding Jolie’s lead, I’ve read enough to know that a double mastectomy is not the best option for every woman who is diagnosed with this gene. Moreover, not every woman who has a double mastectomy gets a boob job. I urge you to discuss your options with your doctor.