For me, it was a profound indictment of American education that only one of my (white) professional colleagues had ever heard of John Hope Franklin before President Bill Clinton appointed him in 1997 to chair the President’s Initiative on Race.

For me, it was a profound indictment of American education that only one of my (white) professional colleagues had ever heard of John Hope Franklin before President Bill Clinton appointed him in 1997 to chair the President’s Initiative on Race.

After all, these were all practicing attorneys who graduated from prestigious liberal arts universities. Never mind that just two years earlier Dr Franklin’s achievements as a professor of American history moved President Clinton to award him the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian award for exceptional meritorious service.

At any rate, Dr Franklin’s scholarly works, especially on Reconstruction and the civil rights movement, figured prominently in my college course on African-American history. Most notable was his classic, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans, which chronicled black life in America.

Of course it may be that, back in the early 1980s, most white students thought that courses in African-American history were only for black students. And that there were no whites in my history class – even though the student body was 95% white – would seem to confirm this.

Yet most Americans would no doubt appreciate the fact that Dr Franklin played a seminal role in the landmark Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which declared the organizing principle of Jim Crowism, “separate but equal,” unconstitutional. After all, this led to the integration not only of public schools in America but also of places of public accommodation.

Using the findings of the historians the lawyers argued that the history of segregation laws reveals that their main purpose was to organize the community upon the basis of a superior white and an inferior Negro caste.

(Dr Franklin)

Perhaps, early in his career, Dr Franklin derived some consolation from the fact that his lectures were much in demand abroad, which garnered him stints in places like China, Zimbabwe and England (Cambridge University). But there’s no denying that he was as pioneering a figure in American education as Jackie Robinson was in American sports. In fact here’s how the New York Times cited just a few of his trailblazing accomplishments:

He was the first African-American president of the American Historical Association; the first black department chairman at a predominantly white institution, Brooklyn College; the first black professor to hold an endowed chair at Duke; the first black chairman of the University of Chicago’s history department; and the first African-American to present a paper at the segregated Southern Historical Association, one of many groups that later elected him its president.

What I found most impressive about Dr Franklin, however, was the fact that he always exuded a Mandela-like serenity despite the many racial indignities he was forced to endure. For example, in an interview with Charlie Rose last year, he nonchalantly recounted how, on the occasion (referenced above) when he came to Washington to receive the Medal of Freedom, a man mistook him for a parking attendant – handing him car keys and telling him to get his car.

What I found most impressive about Dr Franklin, however, was the fact that he always exuded a Mandela-like serenity despite the many racial indignities he was forced to endure. For example, in an interview with Charlie Rose last year, he nonchalantly recounted how, on the occasion (referenced above) when he came to Washington to receive the Medal of Freedom, a man mistook him for a parking attendant – handing him car keys and telling him to get his car.

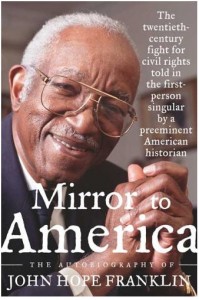

But this story suggests that he was hoping to teach America a lesson even in choosing Mirror to America as the title of his 2005 autobiography. Because I suspect that the subtext of all of his works was aimed at getting white Americans to see the character flaws that gave rise to the institution of slavery and its legacy of racism.

Dr Franklin died of congestive heart failure on Wednesday in Durham, N.C. He was 94.

Farewell Professor

Patrick says

The Lasting Tribute website has updated its memorial pages to include John Hope Franklin.

http://www.lastingtribute.co.uk/tribute/franklin/3050019

It’s a respectful memorial to John and somewhere to pay tribute to the family’s fortitude at this difficult time.

EVERY comment is monitored so that nothing offensive or inappropriate is published.