My heart aches every time there’s a natural disaster or man-made tragedy in some poor country. Not least because it usually results in the deaths of many more (relatively hapless, helpless and hopeless) people than would be the case in some rich country. Think, for example, of the tsunami in Indonesia, the Bhopal gas leak in India, the earthquake in Haiti, or the train derailment in Congo….

I used to feel moved to comment on such disasters and tragedies – until I realized that commenting on them has no more redeeming value than commenting on roadside bombs in Iraq. Even more discouraging, I noticed that most Westerners are as indifferent to them as they are to perennial hunger and strife in Africa.

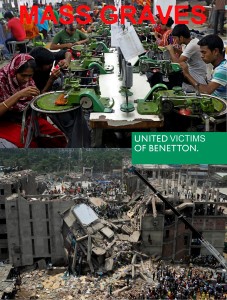

It is with this emotional-intellectual conflict that I watched and read news reports two weeks ago on the collapse of a factory in the garment district of Bangladesh, which is being called the deadliest industrial accident since Bhopal in 1984.

As of today, the death toll is 1,127. Miraculously, a 19-year-old girl was rescued alive from the rubble on Friday, 17 days after the collapse. But this miracle does little to diminish the tragedy of so many much younger girls who were crushed to death.

As of today, the death toll is 1,127. Miraculously, a 19-year-old girl was rescued alive from the rubble on Friday, 17 days after the collapse. But this miracle does little to diminish the tragedy of so many much younger girls who were crushed to death.

In any event, it’s a perverse affirmation of my decision to stop commenting on such tragedies that this factory collapse was preceded in November by a fire in this same district that killed 112, and followed just days ago by another fire that killed eight.

Nonetheless, I feel compelled to register my disgust at the Western companies now threatening to stop doing business in Bangladesh – purportedly because they no longer want to be associated with the substandard building practices that caused the collapse.

The Walt Disney Company, considered the world’s largest licenser with sales of nearly $40 billion, in March ordered an end to the production of branded merchandise in Bangladesh.

(New York Times, May 1, 2013)

Never mind that the PR statements some of them issued in the aftermath of this tragedy betrayed far greater concern about the impact it’s having on their brand than the casualties it caused.

Canada’s Weston family are moving to compensate victims of a deadly building collapse in Bangladesh as reactions to the tragedy goad companies to take greater responsibility for far-flung global supply chains…The image of a label in the rubble of a collapsed factory will spread instantly around the globe…

‘Now we’re waiting for the U.S. brands and all the other European brands to follow suit,’ [said Liana Foxvog, a spokeswoman for the Washington-based International Labor Rights Forum].

(The Globe and Mail, April 30, 2013)

For some reason, though, Benetton is being portrayed as the bad guy in this tragedy. Notwithstanding that its CEO, Biagio Chiarolanza, has reacted in the constructive manner all other CEOs should:

For some reason, though, Benetton is being portrayed as the bad guy in this tragedy. Notwithstanding that its CEO, Biagio Chiarolanza, has reacted in the constructive manner all other CEOs should:

It’s not the solution to go outside from Bangladesh or to think in the future we can leave Bangladesh. I spent some period of my life in this part of the world, and I believe — I really believe — Benetton and other international brands can help these countries improve their condition. But we need a safe and happy working environment and we need to have better conditions.

(Huffington Post, May 9, 2013)

Indeed, despite the exploitation, it behooves us to appreciate that people in poor countries like Bangladesh would be much worse off without the menial wages these companies provide. Not to mention that we have become so dependent on the cheap products cheap labor produces that expecting Westerners to break this vicious and inhumane cycle of co-dependency is even more unrealistic than expecting China to break its dependency on foreign oil.

This is not to say that Western companies should not be morally and legally compelled to improve working conditions and increase wages. I fear, however, that the promises Benetton and others are making in the aftermath of this tragedy might prove just as hollow as those other companies made in the aftermath of previous tragedies.

It’s arguable, for example, that this factory collapse might not have happened if the companies implicated had followed the precedent Apple set in China after its brand became tainted by reports about using cheap labor and slave-like working conditions to produce its popular line of “i” products.

Apple and its China-based supplier Foxconn have agreed to limit worker overtime and significantly improve health and safety conditions at the plants that produce, among other products, the iPhone and iPad. The move comes after an investigation by the Fair Labor Association found Foxconn factories violate numerous Chinese work rules.

(NPR, March 30, 2012)

Meanwhile, such was the moral outage this collapse incited that no less a person than Pope Francis felt moved to condemn the conditions those factory workers were subjected to as tantamount to “slave labor.” He did so during a Vatican mass on May 1. But nowhere was this outrage more visceral and indignant than in Bangladesh. So much so that, despite the risk of sending Western companies shopping for slave labor elsewhere in the developing world:

Bangladesh’s government agreed Monday to allow garment workers to unionize without permission from factory owners. The government also announced plans to raise the meager minimum wage for garment workers, currently $38 a month, which is among the lowest pay in the world for garment workers.

(NBC News, May 13, 2013)

In addition, the government has closed down over 100 factories indefinitely for inspections and repairs. And, to be fair, international labor groups finally prevailed upon major retailers like H&M and Zara today to sign a legally binding agreement to help finance building safety in all factories they use in Bangladesh….

Perhaps this is why some industry experts – including Elizabeth Cline, author of Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion – are countering my cynicism by insisting that this tragedy is “really a turning point.” Because. they say, Western consumers are going to demand more ethical treatment of the workers who produce their cheap products. I say, when pigs fly!

In truth, I’d consider it a triumph of our shared humanity if, whenever you buy self-indulgent products stamped “Made in China” or “Made in Bangladesh,” you merely take a moment to reflect on the exploitation of our fellow human beings that made it possible for you to buy them at rock-bottom prices.